Stair width is one of those dimensions you only really notice when it goes wrong. Too narrow, and you struggle to carry furniture or move safely in an emergency. Too generous, and you lose precious floor area or parking space. When a staircase sits next to a garage, carport or undercroft parking, the balance between compliant stair width and vehicle storage becomes even more critical. Getting it right means understanding how building regulations treat width, how real homes are actually built, and how cars and people share tight spaces. If you are planning a loft conversion, a townhouse with an integral garage or a basement car park, the average width of stairs becomes a key design decision rather than an afterthought.

UK building regulations for stair width: part K, part M and approved document B overview

UK stair regulations focus heavily on safety, consistency and accessibility. While Approved Document K says surprisingly little about an absolute minimum width for domestic stairs, it does anchor width to safe use, handrails and guarding. In parallel, Approved Document M and Approved Document B introduce additional width requirements where access for disabled users and fire evacuation capacity come into play. For private homes, guidance from specialist staircase manufacturers and building inspectors converges around a practical minimum of about 800–860 mm overall width, even though there is technically no hard lower limit in England and Wales. In non‑domestic buildings and common stairs serving multiple flats, standards such as BS 5395‑1 and BS 8300 push widths up to 1,000 mm or more to allow two people to pass and to make evacuation more efficient.

Staircase width is rarely regulated in isolation; it is always tied to how many people will use the stair, how quickly they may need to escape and whether disabled users must be accommodated.

Minimum clear width of domestic stairs under approved document K (england and wales)

In a typical single dwelling, Approved Document K focuses on geometry, rise, going and pitch rather than specifying a strict minimum stair width. Official guidance repeatedly confirms that there is no explicit minimum width for domestic stairs. However, industry practice and building control experience show that widths below about 800 mm quickly become impractical, especially once handrails, strings and wall finishes are included. Many stair specialists therefore recommend an overall stair width around 860 mm, which usually delivers a clear walking line of 750–800 mm between balustrades.

Handrails also influence width requirements. Where a domestic stair exceeds 1,000 mm overall, regulations expect handrails on both sides, which slightly reduces the usable clear width. Stair layout must still respect all the familiar constraints: a maximum pitch of 42°, consistent rise and going, and the 2R+G rule (twice the rise plus the going between 550 and 700 mm). A comfortable domestic stair that feels neither cramped nor excessive usually ends up around 850–900 mm wide, which conveniently matches the clearance needed for moving beds, sofas and white goods.

Stair width provisions for buildings other than dwellings under BS 5395‑1 and part M

Once a stair serves more than one dwelling, or sits in a non‑domestic building such as offices, shops or schools, width becomes more tightly controlled. BS 5395‑1 and Part M steer designers towards effective widths of 1.0 m or more for general access stairs, measured between handrails. In many semi‑public or public buildings, a 1,200 mm to 1,500 mm stair is quite normal, allowing people to pass comfortably and improving accessibility for those using walking aids. Where a stair is wider than 1,800 mm, guidance recommends inserting a central handrail, splitting the effective width into bands between 1,100 mm and 1,800 mm so that users always have a handhold.

On top of this, stairs that must be accessible to disabled people must integrate with level thresholds, ramps and lifts designed to Part M standards. While the regulations allow some flexibility, particularly in constrained refurbishments, a clear commitment to inclusive design is non‑negotiable in new build. From a practical standpoint, if you are sizing stairs for a small office, clinic or shop over a garage, targeting a 1,000–1,200 mm clear width is usually a robust, future‑proof choice.

Fire escape and evacuation stair widths under approved document B and BS 9999

Fire safety guidance treats stair width as a life‑safety parameter, not just a comfort factor. Under Approved Document B and BS 9999, escape stairs must provide enough aggregate width to evacuate the calculated occupant load within a specified time. For small residential buildings, this often means at least one protected stair with a width of around 900–1,000 mm; for larger blocks or commercial premises, widths of 1,200 mm or more are common. The more people on the storey and the fewer escape routes available, the wider each stair must be. In practice, designers often use tabulated flow rates (for example, persons per minute per millimetre of stair width) to size escape stairs precisely.

For homes with integral garages, the internal stair can double as part of the protected route from vehicle storage to habitable rooms. In such layouts, doors between garage and stairwell must generally be FD30 fire doors, and the stair enclosure itself must offer 30 minutes of fire resistance. Although the regulations still do not impose a rigid minimum width, building control officers frequently expect at least 800–900 mm clear width where the stair also acts as the primary escape path from upper floors.

Scottish and northern irish variations in stair width standards (technical handbook, technical booklet H)

Scotland and Northern Ireland adopt their own technical guidance, which broadly mirrors the principles of English and Welsh documents but with subtle differences. The Scottish Technical Handbook introduces an effective stair width of at least 1.0 m for many stairs, though within shared residential accommodation the effective width may reduce to 800 mm where handrails are provided on both sides. The same handbook caps the maximum pitch at 34° for many stairs, leading to longer flights and sometimes influencing how wide a stair can be within a given footprint. Northern Ireland’s Technical Booklet H aligns more closely with Approved Document K but still encourages comfortable widths and proper landings.

Although devolved administrations use different handbooks and numbering, the underlying aim is the same: stairs wide enough to be safe, but not so wide that they become uneconomical or hard to protect from fire.

In cross‑border projects or for designers working across the UK, checking which regional regs apply is essential. A stair that just passes in England might fall short in a Scottish shared stairwell where the 1.0 m effective width rule is triggered. For homes with garages close to the boundary, Scottish guidance on protected routes and external escape stairs can also reshape how wide internal runs can be.

Calculating average width of stairs in residential properties: terraced, semi‑detached and new‑build homes

Ask ten households the width of their stairs and few will know the number, but most will know whether the stair “feels tight” or “feels generous”. Across the UK housing stock, an informal average emerges: around 800–900 mm for domestic flights. Older properties often surprise with slightly broader flights and generous handrails, while compact new‑builds push staircases into ever smaller footprints to free up saleable floor area. For designers and renovators, understanding these typical ranges helps benchmark proposals and judge whether a new stair will feel similar to the rest of the market or noticeably different.

Typical stair width ranges in victorian and edwardian terraces vs post‑1980s housing

Victorian and Edwardian terraces frequently include central staircases of around 850–950 mm overall width. Floor plans from the late 19th and early 20th centuries often show generous hallways and landings, reflecting different lifestyle priorities and less pressure on plot size. In many of these period homes, a clear width of around 800 mm between wall and balustrade is common, which comfortably exceeds what today’s regulations strictly demand. This is one reason why moving large furniture in older terraces often feels easier despite narrower rooms elsewhere.

By contrast, post‑1980s houses, especially volume‑built estates, tend to standardise around widths of 800–860 mm overall. The clear walking line may be as little as 750 mm once plasterboard, skirting and spindles are accounted for. From a building control perspective this remains acceptable, but users often describe these stairs as just adequate rather than generous. In many three‑bed semis, squeezing an integral garage beside this stair further tightens the ground‑floor plan, making accurate dimensioning absolutely crucial.

Optimising stair width in narrow plots and loft conversions under PD rights

Permitted development rights allow many loft conversions and small extensions without full planning permission, but building regulations still apply in full. In constrained terraced houses, the stair to a new loft room is often the hardest element to resolve. You might be tempted to shrink the stair width to “make it fit”, but this can compromise usability and resale value. A practical target for a loft stair is still around 800 mm overall, with a clear width not less than 750 mm; anything tighter begins to feel like a ship’s ladder rather than a comfortable domestic staircase.

Headroom also interacts with width. Over‑tight loft stairs with sloping ceilings sometimes meet minimum headroom only at the centre line, with reduced height at the edges. In these cases, narrowing the stair too far actually reduces the usable area under full headroom, making the stair feel more oppressive. A better strategy is often to adjust the stair position, landing arrangement or roof structure, preserving an 800–850 mm width and compliant 2.0 m (or 1.9 m centre line in lofts) headroom where possible.

Integrating stair width with going, rise and pitch to comply with the 2R+G rule

Stair comfort is not just about width. The rise, going and pitch all play a more important role in how the stair feels underfoot. The famous 2R+G rule – where twice the rise plus the going must fall between 550 mm and 700 mm – provides a simple check. For example, a domestic stair with a 190 mm rise and 240 mm going gives 2×190 + 240 = 620 mm, which sits nicely in the recommended band. Even if the stair is a comfortable 850 mm wide, ignoring this rule risks creating steps that feel too steep or too shallow.

| Stair type | Typical rise (mm) | Typical going (mm) | 2R+G (mm) | Typical width (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Private domestic | 170–220 | 220–260 | 560–700 | 800–900 |

| General access (semi‑public) | 150–170 | 250–280 | 550–620 | 1,000–1,500 |

| Utility / public | 150–170 | 250–300 | 550–640 | 1,200–1,800 |

Designing a stair is therefore a three‑dimensional puzzle: width for passing and furniture; rise and going for comfort; pitch for safety and compliance. Think of width as the lane on a motorway and rise/going as the gradient: both matter, but in different ways. A comfortable “average” domestic stair solves all three simultaneously.

Impact of handrail projection and string thickness on usable stair width

Even when a stair is nominally 860 mm wide, the usable width can be significantly smaller because of strings, handrails and finishes. A typical timber string might be 30–40 mm thick each side. Add plasterboard and skim, and around 60–80 mm disappears before even considering handrails. Standard handrail profiles often project 60–80 mm into the stair width, though Part K expects them to be easy to grip and free from sharp projections.

The result? A stair shown as 860 mm on plan might only feel like 740–780 mm in practice. In garages or tight hallways, this difference can determine whether you can comfortably carry a bike, pushchair or storage box up and down the stair. When you model layouts, always distinguish between overall stair width and effective clear width between obstructions. Careful handrail selection and slim strings can recover valuable millimetres without breaching structural or safety requirements.

Stair width and vehicle storage: integrating internal stairs with garages and carports

Once cars and stairs share the same footprint, every millimetre matters. A standard UK parking bay is usually taken as 2.4 m wide by 4.8 m long, while many family cars now approach 1.9 m in width with mirrors folded. As a result, a single garage of 2.4 m internal width leaves virtually no room for opening doors, never mind a stair. A more realistic internal width for a functional single garage is 3.0 m to 3.2 m, especially where a stair or access corridor shares space. Integrating stair width with vehicle storage in a predictable way is essential for comfortable daily use rather than mere technical compliance.

Minimum stair width for access to integral and attached garages under part M

Where an internal stair doubles as an access route between dwelling and integral garage, Part M treats it as part of the approach to the home. Even though a full “accessible stair” is not always required inside a private house, designers are encouraged to provide stairs that can be negotiated by people with reduced mobility. In practice, this means avoiding extreme narrowness and sharp turns, and providing a clear width that allows someone to use a handrail comfortably while carrying small items. A sensible lower limit remains around 800 mm overall, with 850–900 mm preferred where the stair immediately adjoins a garage door or storage zone.

In many townhouse layouts, a doorway opens from the garage into the stairwell or entrance hall at ground level. The immediate landing area needs to be at least as wide as the stair and deep enough to allow the garage door to open without fouling the stair. Where the stair forms part of the principal route into the dwelling, applying Part M principles such as avoiding steep pitches and providing well‑lit landings reduces the risk of trips in an area already cluttered by tools, bikes and recycling bins.

Designing staircases above or adjacent to vehicle bays for single and double garages

Common layouts place the stair either over the back of a single garage, along one side wall or between two garage bays in a double‑garage arrangement. Each option has implications for both stair width and vehicle manoeuvring. For example, positioning a 900 mm stair along the side of a 3.0 m single garage leaves around 2.1 m for vehicle width – just enough for a compact hatchback but tight for a modern SUV. Shifting the stair partly over the rear quarter of the garage frees lateral width but demands careful headroom coordination beneath the stair.

In a double garage, locating the stair centrally between two 2.4 m bays can help. A 900 mm stair with 100 mm structural wall each side uses 1.1 m, leaving two bays of around 2.45–2.5 m each in a 6.0 m wide shell. This arrangement suits typical UK cars and creates a logical pedestrian route between bays. Of course, beams and columns can constrain this elegant solution, so coordination with structural engineers is essential from the earliest sketch stages.

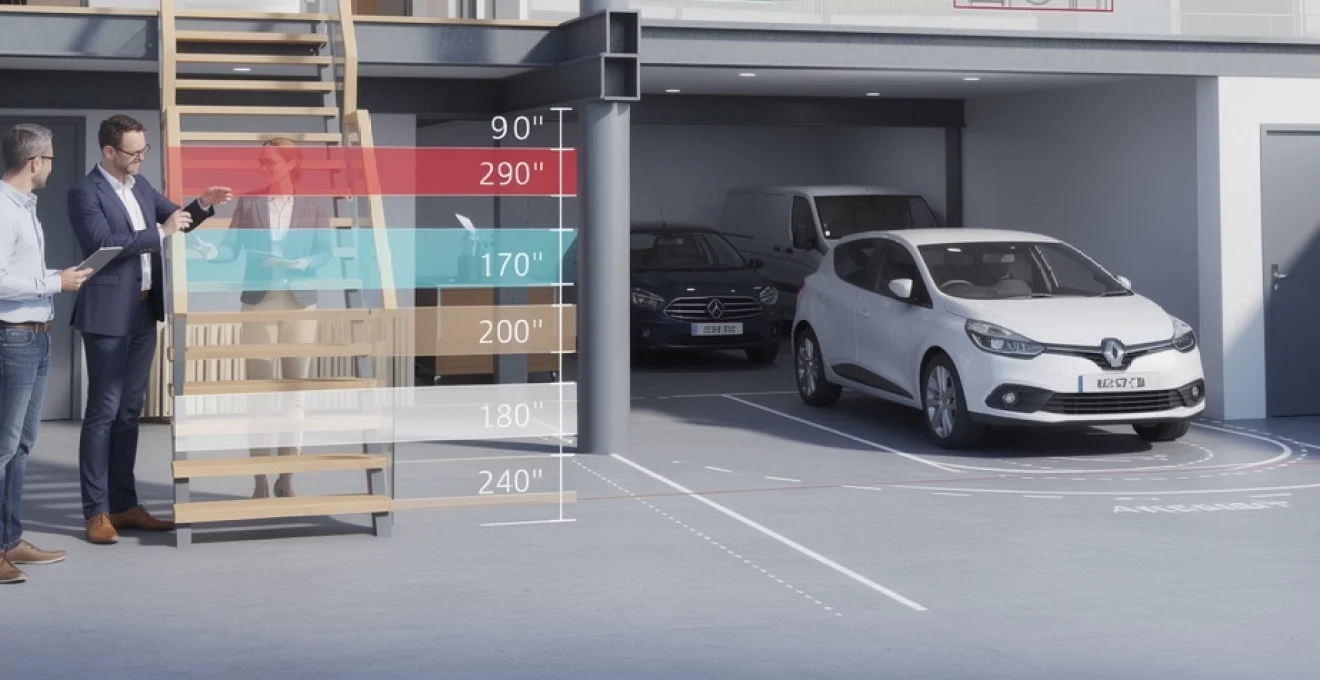

Clearance zones around vehicles (cars, vans, motorcycles) and their interaction with stair width

Vehicle clearance is about more than the static footprint. Door opening arcs, mirrors and turning manoeuvres all nibble at the space available for stairs and access. A modern hatchback like a Ford Fiesta is roughly 1.98 m wide including mirrors, while a VW Golf approaches 2.03 m. A medium Transit van can be 2.27 m wide at the mirrors and around 2.5 m at the mirrors with aftermarket accessories. To exit comfortably, a driver typically needs at least 600 mm between door edge and obstruction on their side.

Imagine a 3.0 m wide garage bay with a stair occupying 900 mm along one wall. That leaves 2.1 m for the vehicle. Even with mirrors folded, the driver may be forced to exit on the passenger side or shuffle into a narrow gap. For garages intended for vans, motorhomes or wide EVs, stair width may need to be balanced against slightly wider garages, say 3.3–3.5 m internal, to avoid daily frustration. Motorcycles and bicycles, by contrast, can slot under or beside stairs more easily, allowing the stair itself to maintain a comfortable width without sacrificing parking functionality.

Case studies: stair–garage layouts in typical 2.4 m, 3 m and 6 m wide UK garages

Design examples help illustrate how tight the relationship between stair width and garage size can be:

- 2.4 m internal “nominal” single garage: any internal stair here is essentially impossible without compromising vehicle use. Even a 700 mm stair would remove the ability to open car doors safely.

- 3.0 m internal single garage with side stair: a 2.1 m vehicle space plus a 900 mm stair is workable for small cars, but door opening is limited. Reducing stair width to 800 mm gives an extra 100 mm for vehicle clearance, often a meaningful difference.

- 6.0 m internal double garage with central stair: two 2.4 m bays and a 1.2 m stair/buffer zone in the middle create a well‑balanced layout. Increasing the stair to 1,000 mm still leaves comfortable bays and improves evacuation capacity.

These scenarios highlight a key design lesson: the “average width of stairs” is not a fixed number but a compromise between human comfort, vehicle size and structural constraints. Treat stair width as a variable within a broader space‑planning equation, not as an afterthought.

Space planning: coordinating stair width with parking bay geometry and turning circles

Successful layouts treat vehicles as moving objects, not just rectangles on a plan. Turning circles, swept paths and door arcs all compete with stair width, lobbies and landings. For tight townhouse sites or basement car parks, a few centimetres trimmed from a stair or added to a bay can decide whether users can park, exit and reach the home comfortably. Thinking in three dimensions, and over time, turns a basic compliance exercise into a robust, user‑friendly design.

Standard vehicle dimensions (e.g. ford fiesta, VW golf, transit van) and circulation allowances

Typical small cars such as the Ford Fiesta have an overall length of around 4.0 m and width of roughly 1.98 m including mirrors. A VW Golf is slightly larger at about 4.28 m long and over 2.0 m wide with mirrors. A short‑wheelbase Ford Transit can reach 5.0 m long and more than 2.2 m wide including mirrors. Standard on‑plot parking bays normally measure 2.4 m by 4.8 m, as used in many planning documents and guidance similar to Manual for Streets.

Good practice allows at least 600 mm free space beside the vehicle for comfortable door opening, preferably 800 mm for disabled drivers. When a stair lobby or landing occupies this side space, its width and door swing must be coordinated. A useful mental model is to picture the car as a stiff suitcase and the stair as a corridor: both need independent clearance if you expect daily life to run smoothly.

Planning internal stairs in basement car parks and undercroft parking

Basement car parks and undercroft parking bring additional constraints. Stairs there often serve multiple dwellings and act as primary escape routes, so widths of 1,000–1,200 mm or more are frequently adopted. At the same time, columns, transfer beams and service risers reduce the freedom to shift stairs around. Designers commonly align stair cores with parking aisles, keeping a clear pedestrian route from bays to cores without cutting through parked‑car envelopes.

In these contexts, the stair width is intertwined with lift lobbies, plant rooms and refuse stores. Guidance akin to BS 5906 on waste management, and contemporary fire strategies, encourages clear separation between vehicle movements and pedestrian access. Providing robust, well‑lit stair cores that remain wide enough to handle evacuation loads – even if a lift is out of service – is now seen as a baseline expectation, particularly in light of evolving fire‑safety scrutiny following recent high‑profile housing incidents.

Designing stair lobbies, landings and door swings adjacent to car parking spaces

Stair width on its own will not solve a poor layout if landings and door swings are mis‑planned. Landings must be at least as wide as the stair they serve and, for domestic situations, deep enough that a door does not swing within 400 mm of a step nose. In car parks, over‑tight lobbies can create awkward bottlenecks where people with bags, pushchairs or wheelchairs struggle to clear inward‑opening fire doors before turning onto the stair.

A practical tip is to draw the full swing of lobby doors and typical car door arcs at 1:50 or 1:20 scale. If any arc crosses into the minimum clear stair width, the layout needs adjustment. This is particularly important where refuge areas for wheelchair users sit adjacent to protected staircases: squeezing the refuge erodes the perceived and actual safety of those waiting for assisted evacuation, even if the formal width metric is barely compliant.

Manual for streets and BS 5906 guidance on pedestrian–vehicle interface near stairs

Modern guidance strongly encourages designers to separate vehicular and pedestrian paths as much as reasonably possible. Documents similar in spirit to Manual for Streets emphasise intuitive layouts, good sightlines and minimal conflict points. Near stairs, this translates into segregated footways from parking bays to cores, adequate lighting and avoidance of blind corners where a reversing vehicle could surprise a pedestrian emerging from a stairwell.

Where pedestrians and vehicles must mix, clarity of routes, generous widths and carefully considered stair placement do more to improve safety than any single sign or line of paint.

BS 5906, while focused on waste management, also touches on circulation in and around refuse stores and car parks. Bin rooms often neighbour stairs near parking levels, and their doors can intrude into access zones if not detailed with care. Giving stairs sufficient width and keeping lobbies free of bins, bikes and ad‑hoc storage preserves the protected route status demanded by building regulations and modern fire strategies.

Structural and fire-safety constraints affecting stair width in vehicle storage areas

Structural grids, fire compartments and smoke control systems all shape what is realistically achievable for stair width in and around garages. A beam that lands 200 mm off an ideal grid line may force the stair to jog, narrowing the available tread width. A thicker wall to achieve 60‑minute fire separation between garage and dwelling may nibble into the stair void. Designers must often juggle these competing requirements, finding a sweet spot where the stair remains wide enough, the garage remains usable and the structure remains efficient.

Load‑bearing walls, beams and columns limiting stair width next to garages

Most houses with integral garages rely on load‑bearing walls and beams over the garage opening, making the garage/stair zone one of the most structurally sensitive areas. Columns or piers beside garage doors may restrict how far a stair can project into the space. Conversely, tilting the stair to clear beams can trigger awkward winders or half‑landings, altering effective width at critical points. A common mistake is designing a generous stair at upper levels only to discover that the ground‑floor structure cannot accommodate the same width without stealing space from the garage.

From a professional standpoint, early coordination between architectural, structural and M&E layouts pays dividends. Modest adjustments to beam depths or column positions can reclaim 50–100 mm of stair width, enough to bring a marginal design back within comfortable tolerances. If widening the stair is impossible, subtle changes to balustrade design or handrail profile can still preserve the clear width needed for compliance.

Fire‑resisting enclosures, FD30 doors and protected routes connecting parking to habitable rooms

Any doorway from a garage into a dwelling normally requires at least an FD30 door with self‑closer and intumescent seals. The wall between garage and stairhall should match this 30‑minute fire resistance, forming part of a protected route to upper floors. These requirements can thicken partitions and nibs by 25–50 mm compared to non‑separating walls, which in turn reduces stair width if the overall footprint is fixed. Yet compromising the fire enclosure to gain a few millimetres of width is not acceptable.

A smarter response is to design the stair enclosure as a coherent fire‑resisting box from the outset, aligning its walls with structural lines. This way, any extra thickness is anticipated rather than retro‑fitted. When dimensioning, measure clear widths inside the finished enclosure, not just the structural shell, to avoid late surprises on site. In multi‑storey car parks or apartment blocks, the same principle scales up: protected stairs may need 60‑minute or even 120‑minute resistance, increasing wall build‑ups and making accurate width planning even more fundamental.

Smoke ventilation, refuge areas and protected stairs in multi‑storey car parks

Multi‑storey car parks bring smoke control into the equation. External or open‑sided designs rely on natural ventilation through large openings, but enclosed structures often need mechanical smoke extract, smoke vents or pressurised stair cores. Protected stairs within these environments are typically wider than in small domestic projects, recognising higher occupant loads and longer travel distances. CLEAR widths of 1,200–1,500 mm are not unusual for main escape stairs in larger car parks.

Refuge areas for mobility‑impaired users usually sit adjacent to these protected stairs, sized to accommodate at least a wheelchair footprint of 900 mm by 1,400 mm plus space to operate communication systems. The stair width must be maintained independent of this refuge space, which means the overall stair‑lobby zone may swell well beyond 2 m clear in one direction. For you as a designer or client, this highlights why squeezing stair width in a car‑dominated building can quickly unravel the wider fire strategy.

Best‑practice design examples: compliant stair widths in homes with integral garages

Translating regulations and theory into working layouts can be challenging. A few benchmark scenarios help illustrate how compliant stair widths and garages can coexist gracefully. Think of these as starting points rather than rigid templates: every site, client brief and local authority will introduce its own constraints and opportunities. Nonetheless, each example underscores one key theme – invest design effort in stairs and vehicle storage early, and both spaces will function far better for decades to come.

Single‑garage townhouse with 800 mm internal stair and under‑stair bike storage

Imagine a three‑storey townhouse, 5.0 m wide, with a 3.0 m internal single garage at ground level and the remaining 2.0 m allocated to entry hall and stair. The stair runs parallel to the garage, with an 800 mm overall width and around 750 mm clear between wall and balustrade. Below the mid‑flight, a recessed zone accommodates bike storage and a small utility cupboard, accessed from the hallway side. The wall between garage and hall is a 30‑minute fire‑resisting partition with a single FD30 door.

This layout balances a modest stair width with viable parking. Small family cars fit within the 3.0 m bay, and bikes can be wheeled under the stair without intruding into vehicle space. For many urban plots, this represents a realistic compromise: the stair is slightly leaner than the “ideal” 860–900 mm but remains safe, compliant and workable for everyday use. If you regularly carry large furniture or bulky sports equipment, though, future‑proofing by nudging the stair closer to 850 mm may be worth the extra design effort.

Double‑garage executive home with 1,000 mm main stair sized for evacuation capacity

In a larger detached home with a 6.0 m by 6.0 m double garage, the design brief might prioritise both generous parking and comfortable circulation. Here, a 1,000 mm clear main stair rises from a central hall directly above the line between two garage bays. Structural beams span over the garage, supporting the stair and first‑floor corridor. The garage is primarily accessed through an external door, with a single internal FD30 door connecting to a side utility room rather than directly into the stairhall.

This arrangement allows two full‑size cars – perhaps an SUV and an estate – to park side by side with sensible clearance, while the main stair remains wide enough to serve as a robust escape route. In a fire strategy for a five‑bedroom house of this type, stair width might be explicitly tied to the estimated occupant load, confirming that 1,000 mm provides sufficient evacuation capacity. From a design perspective, the stair feels luxurious without compromising the garage’s primary function.

Retrofit of compliant stair in existing garage conversion under UK planning and building control

Retrofitting a new stair in a former garage converted to habitable space introduces a different kind of challenge. Many 1960s and 1970s houses have attached garages around 2.7–2.8 m internal width, often repurposed as bedrooms, home offices or annexes. Introducing a stair to a new first‑floor room above often means working within existing walls and foundations. In such projects, designers might accept a slightly reduced stair width of around 800 mm overall, carefully detailed to maximise clear width through slim strings and compact handrail profiles.

Building control will typically focus on consistent rise and going, maximum 42° pitch, headroom of 2.0 m (or permitted loft relaxations) and the creation of a proper fire‑separated route back to the main dwelling. If the converted garage forms part of an independent unit, access stairs might also need to consider Part M guidance for visitable dwellings, nudging widths and landing sizes upward. Treating the stair as a central design element rather than something “squeezed in” leads to conversions that feel integral rather than obviously adapted, adding both value and liveability to the property.