A light van sits at a sweet spot between a car and a truck: big enough to carry serious payload, small enough to be driven on a standard car licence. If you run a business, manage a fleet, or use a van privately, understanding exactly what counts as a “light van” – and the legal specifications that go with it – will save you money, hassle and in some cases, serious legal trouble. Misunderstandings around gross weight, licence categories or tax status regularly lead to fines, unexpected Benefit‑in‑Kind bills or even prosecutions after accidents. Getting clear on definitions, weights, emissions and licensing lets you choose the right vehicle and operate it with confidence.

Legal definition of a light van in the UK and EU vehicle classification

DVLA and DVSA definitions of light commercial vehicles (LCV) versus cars and heavy goods vehicles (HGV)

In UK law, a light van is usually treated as a light commercial vehicle (LCV). HMRC, DVLA and DVSA all use slightly different language, but the common thread is weight and purpose. A typical legal definition is a goods vehicle not exceeding 3,500 kg maximum authorised mass (MAM) that is constructed or adapted to carry goods rather than passengers. Anything over 3,500 kg becomes a heavy goods vehicle (HGV), with tougher rules on licensing, tachographs and operator licensing.

DVLA registration documents (V5C) will normally show a body type such as “panel van”, “light goods vehicle” or, in some cases, “car‑derived van”. That classification influences the speed limits that apply: car‑derived vans under 2 tonnes MAM can follow car speed limits, whereas most other light vans must obey lower van speed limits on single and dual carriageways. DVSA enforcement data shows that over 50% of light goods vehicles stopped at the roadside have serious defects or infringements, which is why light van compliance is receiving far more attention than a few years ago.

EU vehicle categories N1, N2 and M1 and how they apply to light vans

Under EU (and retained UK) type‑approval rules, vehicles are grouped into categories based on design and use. For light vans, the most important are:

N1: vehicles for the carriage of goods with a MAM not exceeding 3,500 kgN2: goods vehicles with MAM over 3,500 kg and up to 12,000 kgM1: passenger vehicles with up to eight passenger seats in addition to the driver

Most modern light vans, including panel vans and chassis cabs up to 3.5 tonnes, are N1 vehicles. However, some crew vans, double‑cab pickups and combis blur the line. They may be constructed as N1 goods vehicles but used like M1 passenger cars. That duality matters for tax and congestion or clean air zone charging, because some schemes treat N1 vans more favourably than M1 cars, and HMRC looks at construction plus actual use when deciding if something is a van for tax purposes.

Gross vehicle weight (GVW) and maximum authorised mass (MAM) thresholds for light vans up to 3.5 tonnes

The terms GVW (Gross Vehicle Weight) and MAM (Maximum Authorised Mass) are crucial. GVW is the actual weight on the road at a given moment; MAM is the legal maximum you are allowed to reach, including the van, fuel, driver, passengers and load. For a vehicle to count as a light van, its MAM must not exceed 3,500 kg. Typical medium panel vans have MAM ratings from 2,700 kg up to 3,500 kg, depending on wheelbase and suspension.

Operating over MAM is treated seriously. DVSA roadside figures show that a high proportion of LGVs are found overloaded, with prohibitions often issued immediately. An overload of more than 15% can lead to prosecution, especially where braking performance or tyre ratings are compromised. If you use a trailer, the relevant threshold is often the combined MAM (vehicle plus trailer), not just the van’s own figure.

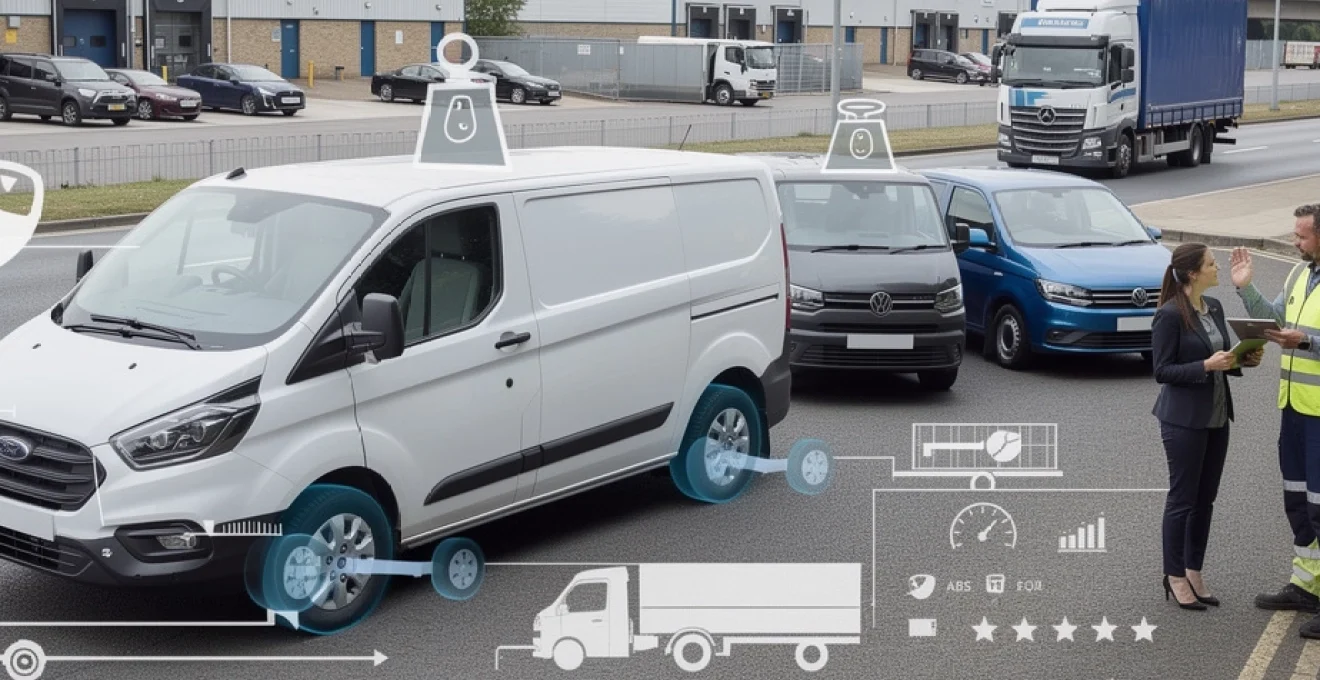

Real-world examples of light vans: ford transit custom, Mercedes-Benz vito, volkswagen transporter, vauxhall vivaro

To put the legal language into context, most of the vans commonly seen on UK roads fall squarely into the light van category. A Ford Transit Custom has MAM options from around 2,600 kg up to 3,400 kg. The Mercedes‑Benz Vito and Volkswagen Transporter T6.1 offer similar gross weight ranges, with high‑roof or long‑wheelbase versions often pushing towards the 3.2–3.5‑tonne mark. The latest Vauxhall Vivaro and Renault Trafic sit in the same segment, with typical payloads between 1,000 kg and 1,400 kg depending on model.

All of these examples are N1 light commercial vehicles for type‑approval purposes. Yet they may be used in very different ways: a fully sign‑written tradesman’s van, a kombi carrying six passengers to site, or a privately owned camper conversion. Legally, that use can change which rules apply to you, especially on tax, insurance and speed limits, even though the base van is identical.

Core legal specifications: weight limits, payload, towing and dimensions

Unladen weight, kerb weight and payload capacity calculations for light vans

To operate a light van safely and legally, you need to know how much it can actually carry. Three figures matter:

- Unladen weight – the weight of the vehicle without fuel, driver or load

- Kerb weight – usually the vehicle with standard fluids, fuel and a nominal driver

- Payload – MAM minus kerb weight; the maximum you can legally add as load

Manufacturers quote payloads in brochures, but those are often for a basic spec van. If you add racking, roof racks, a tail‑lift or refrigeration kit, the real‑world payload drops. A common compliance mistake is to assume the published payload still applies after adding heavy conversions. The most robust approach is to visit a public weighbridge with the van empty, record the actual kerb weight, and then subtract from the plated MAM on the VIN plate to find your true remaining payload.

3.5 tonne MAM limit, tachograph exemption thresholds and operator’s licence implications

The 3.5‑tonne MAM limit is more than a technicality; it is a major legal dividing line. Vans up to 3,500 kg MAM used domestically in Great Britain are generally exempt from EU drivers’ hours rules and tachograph requirements, although some specific operations, such as international carriage for hire or reward in the EU, now bring light vans into scope. The same 3.5‑tonne threshold also determines whether you need a standard goods vehicle Operator’s Licence.

If you operate vehicles over 3,500 kg MAM for business, or a combination of van and trailer that pushes the train weight beyond relevant thresholds, an Operator’s Licence and a nominated transport manager may be required. Many construction and car‑transport operations using heavy trailers behind 3.5‑tonne vans are now facing stricter scrutiny from the DVSA, exactly because these set‑ups can effectively behave like small HGVs without the same safety systems in place.

Legal towing limits, braked and unbraked trailers, and combination weights (GTW) for light vans

Most modern light vans can tow, but the limits vary dramatically. Every vehicle has a plated Gross Train Weight (GTW), which is the maximum combined weight of vehicle plus trailer. In addition, the manufacturer specifies maximum braked and unbraked trailer weights. A typical medium van might be rated to tow a 750 kg unbraked trailer and 2,000–2,500 kg braked, but some variants are lower.

If you exceed the lesser of the GTW or the individual trailer limit, you are committing an offence, even if the actual trailer load is light. Braked trailers must have their own braking system linked to the towing vehicle; unbraked trailers are limited to a maximum of 750 kg MAM. For operators moving plant, vehicles or heavy materials, it is good practice to keep copies of manufacturer towing data in the cab and to train drivers on how these figures work in real‑world loading situations.

Maximum length, width and height requirements under UK construction and use regulations for LCVs

The UK Construction and Use Regulations impose dimensional limits on light commercial vehicles and their loads. For vehicles up to 3.5 tonnes, the maximum overall width is generally 2.55 metres. There is no specific statutory height limit for vans, but vehicles above 3 metres must display a notice in the cab showing the overall travelling height to help drivers avoid bridges and barriers. Length limits depend on whether the van is a rigid or part of a vehicle–trailer combination, but a solo LCV will typically be within the allowed limit if built to standard manufacturer specifications.

Where operators run box bodies, Luton vans or high conversions, attention to height is vital. Bridge strikes remain a costly and dangerous problem, with hundreds of incidents reported on the rail network every year. If you are responsible for a fleet of light vans with differing roof heights, clear signage, route planning and driver training can greatly reduce the risk of incidents.

Axle loads, gross axle weight ratings (GAWR) and load distribution for panel vans and chassis cabs

Every light van has individual gross axle weight ratings (GAWR) for front and rear axles, shown on the VIN plate. Even if the total vehicle weight is within MAM, you can still be illegal if too much load sits over one axle. Panel vans and chassis cabs are particularly vulnerable to rear‑axle overloads when carrying dense cargo far back in the load area or when towing heavy trailers with high nose weights.

Think of the van like a see‑saw: the farther from the centre an item is, the more force it exerts on that axle. To stay compliant, heavy items should be loaded low and as close to the bulkhead as possible, with lighter items above or behind. Simple measures such as marked load zones on the floor and load‑distribution training for drivers can dramatically reduce both enforcement issues and handling problems, especially in wet or emergency braking conditions.

Driver licensing requirements for operating a light van in the UK

Category B, B+E and C1 driving licence entitlements and age-related rules

For most users, the appeal of a light van is that it can be driven on a standard Category B car licence. Category B allows you to drive vehicles up to 3,500 kg MAM with up to eight passenger seats, plus small trailers. Since changes introduced in December 2021, a Category B licence in Great Britain usually entitles you to tow a trailer up to 3,500 kg MAM, subject to the towing capacity of the vehicle itself, effectively replacing the old B+E test requirement for many combinations.

If you regularly need to drive vehicles between 3,500 kg and 7,500 kg MAM, such as larger 7.5‑tonne vans or trucks, you need a Category C1 entitlement. Minimum age rules are generally 18 or 21 depending on the role and whether a Driver CPC is required. For light van users staying at or below 3.5 tonnes, Category B is enough in most scenarios, but checking the back of the photocard for specific entitlements and expiry dates is still essential.

Grandfather rights for pre-1997 licence holders and light van use up to 7.5 tonnes

Drivers who passed their car test before 1 January 1997 enjoy so‑called “grandfather rights”. Their licences often include C1 and C1E categories, allowing them to drive vehicles up to 7.5 tonnes and certain larger combinations without taking an additional test. For businesses operating in rural or niche sectors, this can make older drivers particularly versatile.

However, these entitlements can be lost if the licence is exchanged or renewed incorrectly, or if there is a medical issue. If your operation relies on those rights, it is worth periodically checking that staff still hold the needed categories. Even with grandfather rights, if you are using a vehicle commercially over 3.5 tonnes, Driver CPC and operator licensing rules may still apply, so grandfather rights do not provide a free pass on all professional requirements.

Driver CPC exemptions and when light van operators must hold a driver qualification card

Driver CPC – the Driver Certificate of Professional Competence – applies to most professional drivers of vehicles over 3.5 tonnes in categories C and D. Pure light van operations up to 3,500 kg MAM are typically outside CPC scope. That said, once a van and trailer combination exceeds certain thresholds, or if you step up to a 7.5‑tonner, the requirement may change overnight.

CPC exemptions exist for some non‑commercial activities, such as driving for personal use or certain emergency, agricultural or engineering operations. If you are hovering around the 3.5‑tonne limit with heavy conversions or trailers, seeking professional advice on Driver CPC obligations is wise. Operating without a valid Driver Qualification Card when required can lead to fines for both you and your employer.

Licence implications for towing trailers with LCVs such as a transit custom or renault trafic

Towing with light vans like a Transit Custom, Renault Trafic or Vauxhall Vivaro is common, but licensing and capacity must align. With a standard Category B licence, you may be allowed, in theory, to drive a 3.5‑tonne van and a 3.5‑tonne trailer, but only if the manufacturer’s GTW supports it. In practice, most mid‑sized vans have GTWs in the 5,000–6,000 kg range, limiting real‑world trailer capacity to 2,000–2,500 kg.

If you are driving older licence categories or across borders, rules may differ. Some European countries still have stricter B licence trailer limits based on combined MAM. Before sending a light van and trailer abroad, checking local regulations and ensuring that insurance specifically covers towing is a smart risk‑management step.

Construction, equipment and safety regulations for light vans

Type approval, EC whole vehicle type approval (ECWVTA) and individual vehicle approval (IVA) for LCV conversions

Most new light vans sold in the UK are covered by EC Whole Vehicle Type Approval (ECWVTA), meaning the base vehicle design has been tested and certified to meet safety and environmental standards. When a converter adds a specialist body – such as a refrigerated box, tipper, welfare unit or camper interior – those changes must also be approved, either as part of a multi‑stage type‑approval process or through an Individual Vehicle Approval (IVA) test for one‑off builds.

If you commission bespoke conversions, asking the converter for evidence of type approval or IVA is crucial. Without it, you may struggle to register the vehicle correctly, and insurance could be compromised. In legal disputes after an accident, lack of proper approval for structural changes – for example to seat mounts or bulkheads – can be a serious liability issue.

Mandatory safety equipment: ABS, ESC, airbags, daytime running lights and reversing cameras in modern vans

Modern light vans benefit from a wide range of safety technologies that were rare a decade ago. Anti‑lock braking systems (ABS) and electronic stability control (ESC) are mandatory on new models. Driver airbags are standard, and many manufacturers now fit passenger and side airbags, lane‑keeping assist and autonomous emergency braking systems as standard or optional equipment. Daytime running lights improve visibility, and reversing sensors or cameras are increasingly common.

Although not every feature is legally mandatory on older vehicles, retrofitting basic aids such as reversing cameras can significantly reduce low‑speed collision claims, especially in crowded urban environments. Given that a typical van may cover 20,000–30,000 miles per year, even small improvements in safety and driver awareness often yield measurable reductions in downtime and repair costs.

Load securing rules under EN 12195, lashing points and bulkhead requirements in panel vans

Load security is a major enforcement focus for DVSA. The core principle is simple: the load should stay put under emergency braking, cornering and minor collision forces. Standards such as EN 12195 set out how lashing systems should be designed and rated. A properly designed panel van will include factory‑fitted lashing points in the floor and sometimes on the side walls, along with a fixed or tested bulkhead between cab and load area.

In practice, many operators still rely on inadequate straps or fail to secure items at all. One high‑profile fatal incident involved a scaffolding board swinging out of a light vehicle because it was not properly restrained, leading to a prison sentence for the driver. Treat load restraint as life‑saving equipment, not an afterthought: invest in rated straps, use enough lashing points, and train drivers to check and re‑check loads, especially when using roof racks or towing trailers.

Side guards, rear under-run protection and lighting regulations for UK-registered light vans

Side guards and rear under‑run protection are more closely associated with HGVs, but some heavier 3.5‑tonne LCV chassis cabs with specialist bodies may require similar features to prevent smaller vehicles or pedestrians from going underneath the body in a collision. Lighting regulations, however, apply across all categories. Light vans must have approved headlamps, indicators, brake lights, rear fog lamps and number plate lighting, all kept in good working order.

Additional lighting, such as beacons or work lights, must be installed carefully to avoid dazzling other road users and to remain within Construction and Use requirements. With the growth of electric and hybrid light vans, extra care is also needed when adding electrical equipment, as any device operating while the vehicle moves may need to meet electromagnetic compatibility standards such as R10 certification.

Emission standards, low‑emission zones and ULEZ compliance for light vans

Euro 4, euro 5 and euro 6 emission standards for diesel and petrol light commercial vehicles

Emission standards define how much pollution a light van is allowed to emit when new. The most relevant for today’s fleets are:

| Standard | Typical registration dates (vans) | Main impact |

|---|---|---|

| Euro 4 | c. 2006–2010 | Baseline for older low‑emission zones |

| Euro 5 | c. 2010–2015 | Lower particulates and NOx than Euro 4 |

| Euro 6 | 2016 onwards | Significant NOx reduction; ULEZ compliant in most cases |

Diesel light vans dominate the market and are the main focus of clean air policies because of NOx and particulate emissions. Most city‑centre schemes now require diesel LCVs to be Euro 6 to avoid daily charges, while petrol vans typically need to be at least Euro 4. Checking the emissions standard of a van before purchase, particularly on the used market, is essential if you operate in or near large cities.

Compliance of popular models (e.g. ford transit custom euro 6, VW transporter T6.1) with london ULEZ

London’s Ultra Low Emission Zone (ULEZ) is one of the most influential schemes affecting light van operators. For diesel LCVs, ULEZ compliance generally means meeting Euro 6. A Ford Transit Custom with a Euro 6 engine, a VW Transporter T6.1 or a Mercedes‑Benz Vito Euro 6 model will typically be compliant and avoid the daily charge, whereas older Euro 4 or Euro 5 diesels will be liable for fees each day they enter the zone.

ULEZ boundaries have expanded significantly since launch, and similar schemes across Europe are adopting comparable standards. If your business depends on accessing central London, running non‑compliant vans could easily cost thousands of pounds per year in charges alone. Factoring ULEZ compliance into fleet replacement cycles is now a mainstream strategic consideration, not a niche concern.

Clean air zones in birmingham, bristol, manchester and their impact on older LCVs

Beyond London, a growing number of UK cities have introduced Clean Air Zones (CAZ). Birmingham, Bristol and others operate Class D or Class C zones that charge non‑compliant vans and taxis. The threshold is typically the same as London ULEZ: Euro 6 for diesel and Euro 4 for petrol. Early data from these schemes suggests a rapid shift in fleet composition, with older vans either upgraded, replaced or diverted away from city centres.

If you regularly work across different cities, managing compliance becomes more complex. A van that is acceptable in one area may incur charges in another if local rules or boundaries differ. Creating a simple matrix of fleet age, Euro standard and usual routes can help you decide whether to accelerate replacement, reassign vehicles, or absorb charges temporarily while planning the next procurement phase.

Electric and plug‑in hybrid light vans: vauxhall vivaro‑e, mercedes evito, renault kangoo E‑Tech

The rapid rise of electric light vans changes the compliance landscape entirely. Models such as the Vauxhall Vivaro‑e, Mercedes eVito and Renault Kangoo E‑Tech emit no tailpipe emissions, making them exempt from most low‑emission and congestion charges. Range and payload have improved markedly: many current electric LCVs offer 150–200 miles of real‑world range and payloads close to their diesel counterparts.

For urban multi‑drop work, electric vans can be a strong fit, especially when you factor in fuel savings, reduced maintenance, and potential grants or tax benefits. As more cities announce future bans on internal‑combustion vehicles in their cores, moving early to electric light vans can future‑proof operations and reinforce an organisation’s environmental credentials without sacrificing practicality for short‑to‑medium‑distance routes.

Taxation, insurance groups and commercial use classifications for light vans

HMRC company van tax rules, Benefit‑in‑Kind (BiK) on light vans versus company cars

From a tax perspective, a light van is often far more efficient than a company car. HMRC treats a qualifying company van used for private purposes as a fixed Benefit‑in‑Kind, charged at a flat rate each year (with a separate, relatively small, fuel benefit where free fuel is provided). In contrast, company car BiK is based on the list price and CO₂ emissions, which can be punitive for high‑value, high‑emission cars.

However, HMRC looks closely at whether a vehicle is genuinely a van. Double‑cab pickups, crew vans and combis are scrutinised; if the passenger‑carrying capacity dominates and payload after accounting for passengers is under one tonne, HMRC may class the vehicle as a car. That reclassification can multiply the tax bill for both employer and user, so documenting payload and primary use is sensible when operating borderline vehicles.

VED (road tax) bands and CO₂‑based charging for light commercial vehicles

Vehicle Excise Duty (VED), often called road tax, works differently for vans than for cars. Many light commercial vehicles fall into a flat‑rate van class rather than the CO₂‑graded car bands, especially if registered before certain cut‑off dates. More recent N1‑category vans with type‑approved CO₂ values may fall into CO₂‑linked bands, but the structure remains simpler than for passenger cars.

The overall effect is that annual VED for a light van is often lower and more predictable than for an equivalent‑value car, particularly high‑CO₂ models. That said, as governments push harder on emissions, future reforms may tighten the link between van taxation and CO₂ output. Choosing Euro 6 or zero‑emission vans today already offers advantages in many city schemes and could also cushion against future VED changes.

Commercial vehicle insurance classes, carriage of own goods versus hire and reward

Insurance for light vans is not simply “more expensive car insurance”. Policies are grouped into distinct commercial classes, often including:

- Carriage of own goods – for tradespeople transporting tools and materials they own

- Hire and reward – for couriers, delivery drivers or anyone paid specifically to transport goods

- Haulage – for longer‑distance freight carriage

Choosing the wrong class can invalidate cover. If you use a light van initially for your own trade but later start offering paid delivery services, you must update the insurer. Many policies also impose conditions on overnight parking, security and use by multiple drivers. Reading the schedule and endorsements in detail, rather than assuming van insurance works like private car cover, is a key risk‑management step.

VAT treatment, capital allowances and van versus car classification for double‑cab pickups

For VAT and capital allowances, the distinction between a van and a car is critical. If a light vehicle is classed as a van, businesses can usually reclaim VAT on purchase or lease (subject to normal rules) and claim capital allowances more flexibly. With a car, VAT recovery is heavily restricted unless the vehicle is used 100% for business. HMRC guidance effectively requires double‑cab pickups to have a payload of at least 1,000 kg to be treated as vans for most tax purposes.

Adding a heavy hard‑top or accessories can inadvertently reduce the official payload below that 1‑tonne threshold, turning a “van” into a “car” in HMRC’s eyes. That change can affect VAT reclaim, capital allowances and BiK. When speccing or modifying double‑cab pickups or crew vans, checking how changes affect unladen weight and payload is not just a technical exercise; it directly impacts the long‑term cost of ownership and tax efficiency.