Ask ten people which region Lincolnshire belongs to and you may hear three different answers: the Midlands, the North, or simply “out on its own”. The county stretches from the Humber to The Wash, from the Lincolnshire Wolds to the Fens, so its geography and culture often blur neat categories. Yet for planning, statistics and investment decisions, Lincolnshire’s regional status matters a great deal. It shapes how funding is allocated, how services are organised and even how you might analyse business opportunities, migration patterns or quality of life here. Understanding exactly where Lincolnshire sits within the UK’s regional framework helps you interpret data correctly, plan travel, explore jobs or relocation options, and appreciate why this large, often underestimated county plays such a strategic role between the Midlands, Yorkshire and the North Sea coast.

Administrative region: locating lincolnshire within england’s official regional structure

Positioning lincolnshire in the east midlands region under current UK regional classifications

Under current UK government and ONS classifications, Lincolnshire (the main non‑metropolitan county with Lincoln as its city) sits firmly within the East Midlands region. The East Midlands covers around 15,600 km², about six percent of the UK land area, and includes the counties of Derbyshire, Leicestershire, Lincolnshire, Northamptonshire, Nottinghamshire and Rutland. Together, these areas formed one of the former government office regions used for regional planning, funding and statistical comparisons. Lincolnshire shares this official regional label with cities such as Nottingham, Leicester and Derby, even though its landscape and settlement pattern are far more rural and coastal in character.

The East Midlands population reached roughly 4.99 million in 2023, representing about 7.2% of the UK population, and Lincolnshire contributes a significant share of this total. Around 29.5% of East Midlands residents live in rural settlements, making it the third most rural English region, and Lincolnshire is a major reason for that statistic. When you see labour market data or economic indicators broken down by “East Midlands”, Lincolnshire’s figures are baked into those regional averages, influencing perceptions of everything from employment rates to health outcomes.

Historic county of lincolnshire versus modern east midlands regional governance

The historic county of Lincolnshire predates the modern East Midlands framework by many centuries. Historically, the county formed a large administrative and cultural unit, linked more to the ancient kingdom of Lindsey and the Danelaw than to bureaucratic regions. Modern East Midlands structures emerged largely in the late 20th century as national government sought to create larger regions for economic planning and EU statistical reporting. As a result, a historic county with its own long‑standing identity now sits inside a regional framework designed mainly for policy coordination and data comparison.

For you as a resident, business owner or researcher, this duality can be confusing. Older documents, local traditions and some cultural references still treat Lincolnshire as a distinct, almost self‑contained entity. Newer policy papers and funding programmes refer to Lincolnshire as part of the East Midlands, grouping it with urban centres like Nottingham and Leicester. Treat the historic county as the cultural layer, and the East Midlands region as the administrative layer that overlays it; both matter, but they answer different questions.

Lincolnshire’s unitary authorities (north lincolnshire, north east lincolnshire) and their regional alignment

Complicating the picture further, the ceremonial county of Lincolnshire includes three main components: the non‑metropolitan county of Lincolnshire, plus the unitary authorities of North Lincolnshire and North East Lincolnshire. Administratively, those two unitary authorities are not in the East Midlands region; they are aligned with the Yorkshire and the Humber region for many government and statistical purposes. That means Scunthorpe, Grimsby and Cleethorpes are regionally counted with areas like Hull and the East Riding of Yorkshire rather than with Lincoln or Grantham.

This split can matter significantly when you look at regional funding or economic strategies. For example, North Lincolnshire and North East Lincolnshire may be eligible for initiatives targeted at Yorkshire and the Humber, while the rest of Lincolnshire participates in East Midlands‑focused programmes. If you compare job figures, earnings or deprivation statistics, you should always check whether a dataset refers to the ceremonial county of Lincolnshire or to the specific local authorities aligned with different regions; the distinction changes how you interpret the numbers.

ONS (office for national statistics) regional coding for lincolnshire within NUTS and ITL frameworks

The Office for National Statistics uses NUTS and now ITL (International Territorial Levels) codes to classify UK territories for statistical purposes. Under these frameworks, the East Midlands is one of the higher‑level regional units, within which Lincolnshire (county) appears as a lower‑tier area. Meanwhile, Greater Lincolnshire sometimes appears as a combined authority area, drawing together Lincolnshire County Council and the two northern unitary authorities, even though they straddle two official regions.

On the ONS “Explore local statistics” service, you will find an entry for Greater Lincolnshire as a combined authority area, with local indicators for health, education, economy and more. This reflects a growing recognition that economic geography does not always match strict regional boundaries. If you work with regional data, treating Greater Lincolnshire as a functional economic region while still acknowledging distinct ONS regional codes is usually the most accurate way to understand commuting, housing markets or industrial clusters in this part of England.

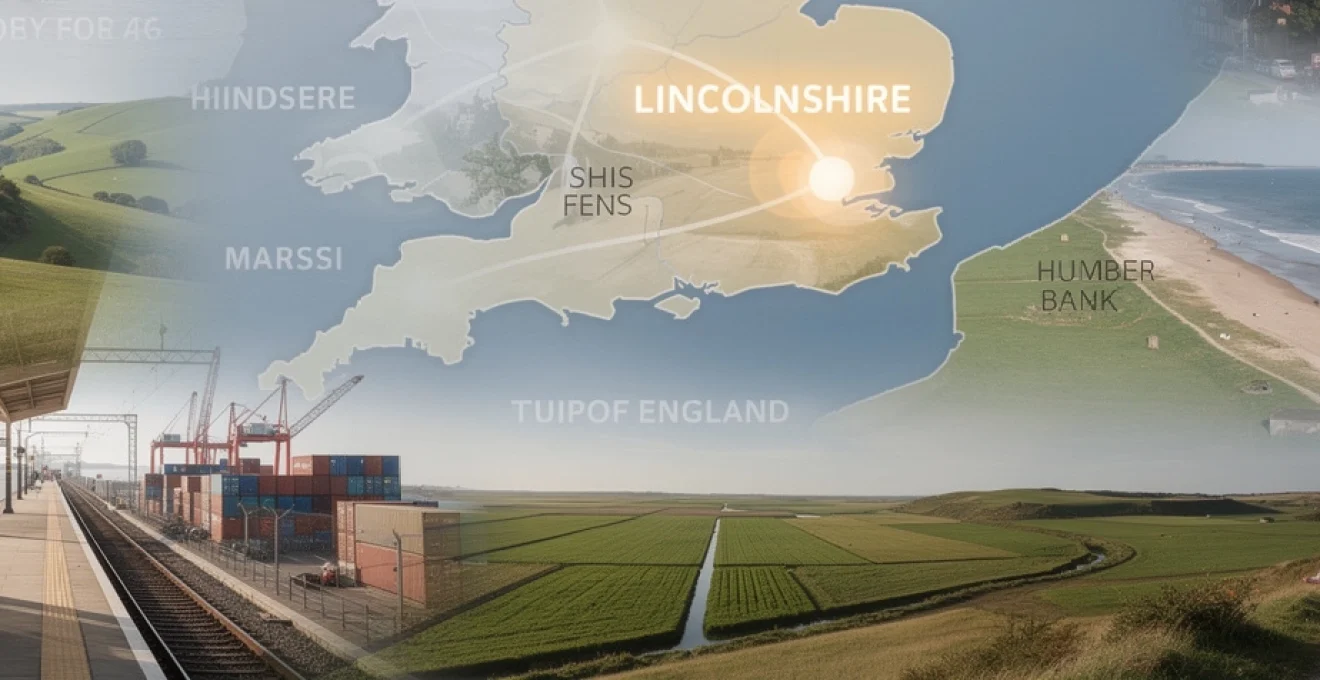

Geographical boundaries: mapping lincolnshire’s borders with yorkshire, nottinghamshire and the north sea

Defining lincolnshire’s northern boundary along the humber estuary and the border with the east riding of yorkshire

Lincolnshire’s northern edge is dominated by the wide Humber Estuary, a major maritime gateway and one of the UK’s most important estuarine landscapes. On the south bank of the Humber sit towns such as Barton‑upon‑Humber and Immingham, facing across to Hull and the East Riding of Yorkshire on the opposite shore. This estuary forms both a natural and administrative boundary, linking Lincolnshire economically to Yorkshire while also dividing the two counties physically.

To the north‑east, the border with the East Riding of Yorkshire cuts inland east of the Humber Bridge, while to the north‑west the county meets South Yorkshire around areas connected by the River Don and River Trent corridors. The Humber’s strategic role as a shipping and logistics hub has long tied Lincolnshire’s northern fringe into the wider Humber sub‑region, which explains why North and North East Lincolnshire align administratively with Yorkshire and the Humber rather than the East Midlands. When you think about northern Lincolnshire, imagine it as the southern anchor of the Humber region.

Western boundaries with nottinghamshire, south yorkshire and the river trent corridor

On its western side, Lincolnshire borders Nottinghamshire and South Yorkshire, with the River Trent playing a crucial role in defining parts of this boundary. The Trent corridor has historically served as both a barrier and a transport route, guiding trade and movement between the Midlands and the Humber. Towns like Gainsborough and Crowle illustrate how closely linked western Lincolnshire is to neighbouring counties through road, rail and river crossings.

These western borders give Lincolnshire direct land connections to major urban centres such as Nottingham and Sheffield. As a result, commuter flows and labour market ties often run westwards, even though Lincolnshire itself remains largely rural. Statistically, this western edge is where East Midlands and Yorkshire labour markets interact, making it a key zone if you are analysing commuting patterns or looking at cross‑boundary housing markets.

Southern interfaces with cambridgeshire, norfolk and the fens drainage landscape

To the south, Lincolnshire meets Cambridgeshire, Norfolk, Rutland and Northamptonshire across the low‑lying Fens and gently rolling uplands. The Fens are a shared landscape, stretching seamlessly across administrative borders into Cambridgeshire and Norfolk, and united by centuries of drainage and land‑reclamation schemes. This is one of Europe’s most important agricultural regions, with rich soils supporting intensive farming and food production that serves both domestic and export markets.

Because the Fens cut across multiple counties, regional boundaries here feel less visible on the ground. If you drive south from Spalding or Holbeach into Cambridgeshire, the flat, drained landscape continues almost unchanged. What does change, however, is the regional coding: you move from the East Midlands into the East of England. For economic modelling or environmental planning, it is often more accurate to treat the Fens as a single ecological and agricultural system rather than focusing solely on county lines.

Eastern maritime boundary along the north sea coast from cleethorpes to gibraltar point

Lincolnshire’s eastern boundary is its long North Sea coastline, running from the Humber mouth near Cleethorpes down to Gibraltar Point and beyond towards The Wash. This coast includes popular resorts such as Cleethorpes, Skegness, Mablethorpe and Chapel St Leonards, alongside quieter stretches of marsh, dunes and nature reserves. The coastal strip forms a distinctive sub‑region, combining tourism, fishing and nature conservation with vulnerability to coastal erosion and flooding.

The North Sea boundary also frames Lincolnshire’s role in offshore energy, shipping routes and marine conservation. As the UK accelerates investment in offshore wind and coastal defences, Lincolnshire’s coast is becoming a frontline area for climate adaptation and energy infrastructure. For anyone considering tourism development, coastal living or environmental projects, understanding this maritime edge is essential to appreciating how Lincolnshire connects to wider North Sea and North European networks.

Ceremonial county and lieutenancy area: how lincolnshire is classified for formal UK functions

The ceremonial county of Lincolnshire is the unit used for formal functions such as the Lieutenancy, High Sheriff appointments and some judicial and civic roles. It combines the non‑metropolitan county of Lincolnshire with the unitary authorities of North Lincolnshire and North East Lincolnshire. In other words, from a ceremonial perspective, places as far apart as Stamford, Scunthorpe and Grimsby belong to the same overarching county. This ceremonial county is assigned a specific Lieutenancy area, used for royal visits, honours and other official duties.

This dual identity – one county for ceremony, but split for administrative regions – is a good example of how British territorial organisation layers different systems on top of each other. For you, this matters when reading reports that reference the “ceremonial county of Lincolnshire” rather than individual local authorities. Population counts, for instance, may draw on combined figures, even though North Lincolnshire and North East Lincolnshire sit in the Yorkshire and the Humber region for many policy decisions. Treat ceremonial boundaries as the “big picture” county, and local authority borders as the working units for services, taxation and planning applications.

| Area type | Includes | Regional alignment |

|---|---|---|

| Non‑metropolitan county of Lincolnshire | Lincoln, Boston, Grantham, Skegness, Louth, Sleaford, Spalding, etc. | East Midlands |

| North Lincolnshire (unitary) | Scunthorpe, Brigg, Barton‑upon‑Humber, Epworth, Crowle | Yorkshire and the Humber |

| North East Lincolnshire (unitary) | Grimsby, Cleethorpes, Immingham | Yorkshire and the Humber |

| Ceremonial Lincolnshire | All three of the above combined | Single Lieutenancy area |

From a demographic point of view, Greater Lincolnshire is often treated as a combined area, especially in economic partnerships and strategic documents. For instance, gross weekly pay figures highlight how the wider East Midlands, including the core of Lincolnshire, has lower average earnings than the UK (£647 versus £728 per week), and regional profiles usually discuss Greater Lincolnshire within that context. When you see statistics for “Greater Lincolnshire”, they normally integrate data from the county council area and the two unitary authorities, acknowledging the reality that residents and businesses operate across administrative lines daily.

Sub‑regions within lincolnshire: wolds, fens, marsh and humber bank industrial belt

Lincolnshire wolds AONB and its relationship to the wider east midlands upland landscape

The Lincolnshire Wolds form a chain of rolling hills stretching roughly north‑south through the county, designated as an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB). Despite Lincolnshire’s reputation as flat, the Wolds provide a rare upland landscape within the East Midlands, linking visually with higher ground in neighbouring counties. This area has a distinct rural economy based on mixed farming, small market towns such as Louth and Caistor, and growing outdoor recreation and tourism.

If you are considering rural tourism or place‑based branding, the Wolds offer a powerful counterpoint to the stereotype of Lincolnshire as only fens and marsh. The area’s protected status also means planning decisions are more tightly controlled, balancing development opportunities with landscape and heritage conservation. In regional strategies, the Wolds frequently appear as a key asset for green tourism and nature‑based wellbeing in the East Midlands.

Lincolnshire fens as part of the greater fens ecosystem shared with cambridgeshire and norfolk

The Lincolnshire Fens occupy a large swathe of the south‑eastern county, forming part of the broader Fens system that continues into Cambridgeshire and Norfolk. Drained over centuries through an evolving network of dykes, pumps and rivers, this landscape has become one of the UK’s most productive agricultural zones. Towns such as Boston, Spalding, Holbeach and Long Sutton sit at the heart of this intensely farmed region, where horticulture, vegetable growing and food processing dominate the local economy.

From a regional geography perspective, the Fens blur administrative lines but reinforce functional connections along drainage channels and transport routes. If you work in agriculture, logistics or environmental management, understanding the Lincolnshire Fens as part of a cross‑county system is crucial. Issues such as flood risk, soil health and migrant labour patterns affect the entire Fens, not just the Lincolnshire portion, and require joined‑up planning that transcends strict county borders.

Lincolnshire marsh and coastal strip including skegness, mablethorpe and chapel st leonards

Between the Wolds and the North Sea lies the Lincolnshire Marsh, a low‑lying coastal plain that supports a mix of agriculture, tourism and residential communities. Resorts such as Skegness, Mablethorpe and Chapel St Leonards form a distinctive seaside belt, attracting visitors from the East Midlands, Yorkshire and beyond. For many families, this stretch of coast provides an affordable, accessible alternative to more expensive southern resorts, anchoring Lincolnshire firmly in the UK’s coastal tourism region.

The marsh and coastal strip face particular challenges, including seasonal employment patterns, coastal erosion and flood risk linked to climate change. Yet they also offer opportunities in nature‑based tourism, blue‑green infrastructure and renewable energy. If you are analysing Lincolnshire’s economy, recognising this coastal sub‑region as a separate but interconnected zone helps explain why some local indicators – such as seasonal unemployment or health outcomes – differ from inland areas.

Humber bank and south humber industrial zone around grimsby, immingham and scunthorpe

To the north, the Humber Bank and South Humber industrial zone form one of Lincolnshire’s most industrialised and urbanised sub‑regions. Grimsby, Immingham and Scunthorpe anchor this belt, hosting major port facilities, heavy industry, logistics operations and a renowned seafood processing cluster. The ports around Immingham are among the UK’s busiest by tonnage, while Scunthorpe has long been a key steel‑producing centre.

This sub‑region connects Lincolnshire directly into national and international supply chains, from car manufacturing to energy imports. It also illustrates why Greater Lincolnshire cannot be understood solely as a rural county with agriculture and tourism; the industrial belt around the Humber is central to UK logistics and manufacturing resilience. For investors, policy‑makers or job‑seekers, recognising this dual character – rural heartland plus heavy industry – is essential to understanding Lincolnshire’s wider role in the UK economy.

Economic and transport region: lincolnshire’s integration with east midlands and yorkshire networks

Commuter flows between lincolnshire, nottingham, sheffield and hull in labour market statistics

Labour market data for the East Midlands and Yorkshire shows how Lincolnshire’s workforce interacts with neighbouring cities. The regional labour force participation rate stands at around 74.6%, only slightly below the UK average, with about 75.5% in employment and 3.7% unemployed at the end of 2023. Yet within those averages, commuting patterns tell a more nuanced story. Many residents of western and northern Lincolnshire travel to Nottingham, Sheffield or Hull for work, while coastal and fenland communities remain more locally focused.

Why does this matter to you? If you are assessing job prospects or planning a move, the travel‑to‑work areas around Lincoln, Grantham and Gainsborough link strongly into the broader East Midlands conurbations. In contrast, Grimsby and Scunthorpe sit within Humber‑focused labour markets. The result is a patchwork of overlapping economic regions, which helps explain why a combined authority label like “Greater Lincolnshire” has real practical meaning even though parts of it fall into different official regions.

Understanding commuter flows across Greater Lincolnshire and neighbouring cities is vital for designing transport investment, housing policy and skills programmes that actually match how people live and work.

Strategic road and rail corridors: A1, A15, A16, A46, east coast main line and regional connectivity

Lincolnshire’s strategic position between the Midlands, Yorkshire and the East of England is reinforced by key road and rail corridors. The A1 and A46 offer fast links from the south, making journeys from the London and Peterborough direction quicker and more reliable than in the past. From the north and north‑west, the M180 connecting to the A15 supports a seamless drive into northern Lincolnshire and towards Lincoln itself. Towns such as Lincoln, Sleaford and Grantham also benefit from proximity to the East Coast Main Line, giving relatively direct rail connections to London, the North East and Scotland.

For you as a visitor, commuter or business planner, these corridors turn Lincolnshire from a supposedly “remote” county into a surprisingly accessible one. Journey‑time reductions on roads like the A46, along with direct rail services from major cities such as Leicester, Leeds and London, reduce the perception gap between map distance and travel time. When combined with investment in digital infrastructure, this connectivity underpins Lincolnshire’s role as a bridge between regional economies rather than a peripheral backwater.

Humber freeport, immingham docks and grimsby seafood cluster as cross‑regional economic assets

The designation of the Humber Freeport has highlighted Lincolnshire’s cross‑regional economic importance. Immingham Docks and associated port facilities form a core part of this freeport zone, streamlining customs processes and encouraging inward investment across manufacturing, energy and logistics. The Grimsby seafood cluster remains one of Europe’s largest concentrations of seafood processing and distribution businesses, linking North Sea fisheries, international imports and UK retailers.

These assets serve both the East Midlands and Yorkshire and the Humber, effectively knitting the two regions together through supply chains and trade flows. If you operate in logistics, manufacturing or food processing, the Humber Bank area offers a strategic base that taps into multiple regional markets. At the same time, it reinforces the argument that traditional regional labels only partially capture how Lincolnshire functions in the wider UK economy.

Visit lincolnshire tourism zone within the broader east of england and coastal tourism regions

Tourism bodies and marketing campaigns often treat Lincolnshire as a distinct visitor region while also linking it into larger coastal and countryside offers. The county’s variety – from the cathedral city of Lincoln to seaside resorts and rural market towns such as Stamford, Horncastle and Woodhall Spa – allows visitors to experience multiple landscapes within a relatively compact area. In practice, many tourists combine Lincolnshire trips with visits to neighbouring areas like Nottinghamshire, Yorkshire’s coast or the Norfolk Fens, creating a functional “East of England and East Midlands” coastal tourism belt.

If you run a tourism business or plan a holiday, it is helpful to think about Lincolnshire as part of several overlapping tourism regions: the East Midlands countryside, the North Sea coast, the Fens, and the Humber estuary. Each brings different visitor expectations and travel patterns, but all share Lincolnshire as a central thread. This multi‑regional positioning supports diverse tourism products, from heritage city breaks and cycling in the Wolds to family beach holidays and nature watching along the marshes.

Cultural and historical context: danelaw, lindsey and lincolnshire’s regional identity in england

Anglo‑saxon kingdom of lindsey and its role in shaping lincolnshire’s historic region

Long before modern administrative regions existed, the area now known as Lincolnshire formed much of the Anglo‑Saxon kingdom of Lindsey. Centred on Lincoln, Lindsey acted as a buffer and bridge between Northumbria and Mercia, reflecting the same “in‑between” character that Lincolnshire still has today between North and Midlands. Archaeology and place‑names across the county bear witness to this early political entity, which contributed to Lincoln’s later importance as a medieval cathedral city and trading hub.

If you are interested in how historic regions shape modern identity, Lindsey provides a powerful example. The idea that Lincolnshire forms its own distinct block, separate from both Yorkshire and the central Midlands, can be traced back to this early kingdom. Modern regional classifications may place Lincolnshire in the East Midlands, but deep‑rooted patterns of settlement, parishes and landholding still echo the earlier Lindsey framework.

Danelaw, viking settlements and the origins of place‑names such as grimsby and ormsby

During the Danelaw period, large parts of what is now Lincolnshire came under Viking control and settlement. This legacy is still visible in the names of many towns and villages ending in -by, such as Grimsby, Ormsby and Mablethorpe’s neighbouring settlements. The Danelaw frontier cut across what are now East Midlands and Yorkshire regions, reminding you that historical cultural zones rarely match modern administrative borders.

The density of Scandinavian place‑names across Lincolnshire illustrates how strongly the Danelaw shaped local identity, language and land organisation, leaving a cultural imprint that outlived the political arrangement itself.

For modern regional identity, this Norse heritage gives Lincolnshire a flavour that some residents feel aligns more closely with the North and Yorkshire than with the Birmingham‑centred Midlands. Festivals, local history projects and heritage tourism around Viking and medieval themes draw on this shared Danelaw narrative, reinforcing Lincolnshire’s image as part of the historic North Sea world rather than simply an inland Midlands county.

Medieval and early modern lincolnshire in relation to the midlands and northern england

In medieval and early modern periods, Lincolnshire’s economic and political links ran in several directions. Wool and agricultural products flowed through Lincoln and Boston to continental Europe, while ecclesiastical networks connected the county to both York and Canterbury. Over time, as industrialisation took hold more strongly in the West Midlands and the North, Lincolnshire retained a predominantly rural, agrarian character, with only limited heavy industry outside the Humber Bank and a few urban centres like Grantham.

This historical trajectory helps explain why, in the 20th century, Lincolnshire could be plausibly grouped either with the Midlands or with Northern England depending on the perspective taken. Economically, the county looked more like northern rural areas; administratively, it made sense to align it with an East Midlands region focused on cities such as Nottingham and Leicester. Today’s mixed identity is therefore not a recent invention but the latest phase in a long history of ambivalent regional positioning.

Contemporary regional identity: “yellowbelly” culture and alignment with midlands versus north

Contemporary Lincolnshire identity often revolves around the affectionate nickname “Yellowbelly” for local people, along with strong pride in the county’s dialects, food and landscapes. Ask residents whether Lincolnshire belongs in the North or the Midlands, and you will hear varied answers – some see strong cultural ties with Yorkshire and Humberside, others feel a closer affinity with the East Midlands and cities like Nottingham. Many simply identify as “from Lincolnshire”, treating the county as a region in its own right.

From a professional perspective, this layered identity has practical implications. Public health campaigns, for example, need to recognise that East Midlands averages mask local challenges: East Midlands residents, including many in Lincolnshire, have slightly poorer health than the national average and are more likely to face issues such as obesity or circulatory diseases, even though cancer mortality is lower. At the same time, the region’s relatively low job density (around 0.79 jobs per working‑age person, compared with 0.95 for the UK) and below‑average wages shape how people view prospects and regional fairness. Understanding Lincolnshire’s identity means looking beyond labels to how residents experience work, community and place – an experience that feels simultaneously Midlands, northern and uniquely “Yellowbelly”.